From Workers International News, Vol.7 No.3, October 1947, pp.12-20.

Transcribed by Ted Crawford.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

This is the first of three articles on the role of the United States in the world economy. [1] The second will deal with the problem of Europe’s economic-political situation and its effects on US economic policy. The third will deal with the conflict between Russia and the United States and the strategy of US imperialism in its preparations for the inevitable war with Russia if capitalism is not overthrown.

***********

In the nineteenth century, United States economy was subordinate to European capitalism. With her population swelled by the absorption of tens of millions of ruined peasants, artisans, unemployed workers, etc. who migrated from Europe, she became the biggest market for European, in the main British, industry. She also developed into the biggest field for capital investment and was an important source of cheap raw materials and foodstuffs. Endowed with unbounded natural wealth, unhampered by feudal impediments to the development of the productive forces, and with the masses enjoying a relatively high standard of life which compelled the American capitalists from the beginning to base themselves on a developed technique, America could readily absorb all the European labour power, commodities and capital that streamed towards her shores.

The same factors, however, also explain why, in the space of a few decades, her colonial character disappeared and she transformed herself into the mightiest imperialist economy. Already in the 1880’s, the United States produced the greatest volume of industrial products of all industrial countries. In 1914, she produced 35 per cent of world industrial production, while the whole of Europe produced 53 per cent.

The greatest changes in the relations between the US and world economy took place during the first world war when Europe’s industrial production declined by a third, and United States production rose by about a quarter. From a debtor country she became a creditor country, second only to the United Kingdom. The end of the first world war saw America supplying more than 40 per cent of world industrial products.

The increasing weight of United States capitalism in world economy was even more clearly revealed in the 1922-29 boom, in which American loans played a role of prime impatience. In 1929, United States national income in terms of dollars was as big as that of the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, and another 18 countries together. (This evaluation should really be modified by taking into account the fact that US prices were higher than in the rest of the world in general, and this would somewhat diminish the relative magnitude of her national income.) In the years 1919-29 the United States tied world economy to herself through the loans she gave to other countries, which were far greater than those given by Britain, France, Holland, and the other imperialist countries together. But even more clearly than in the stabilisation of the 20’s did the subordination of world economy to that of the United States reveal itself in the crisis and depression of the 30’s the crash in Wall Street was a major shock to world capitalism.

During the second world war, the shift in the relation of forces followed the same tendency as before the and was much more accelerated. While European production declined, United States production rose by more than 50 per cent. While in Europe towns were devastated, in the United States 24 new towns arose. Millions of workers migrated to new regions whose economic importance increased. Thus, for instance, the district of Los Angeles which before the war was mainly agricultural and contained only a small number of light industries – films, cosmetics, furniture, etc, – became an important centre of heavy industry. This district alone annually produced double the number of aeroplanes than the whole of Germany produced, and four times the number that Japan did! The new shipyards of California in one year built more ships than the rest of the world together. We can safely say that United States production today accounts for at least two thirds of world industrial production.

In the nineteenth century, to understand the development of the United States, one had to begin with an analysis of world economy; today, to understand the development of world economy one must begin by analysing the economy of the United States. Let us, therefore, first examine the internal contradictions in American economy at the end of the second world war.

During the Second World War, US production rose more than 50 per cent (1939-44) – an enormous disproportion between the rise in production and the rise in consumption. This means that the rate of accumulation increases relatively to consumption and to wages, and consequently that the process of increasing disproportion between production and consumption is cumulatively accelerated. The fact that the equilibrium of United States economy did not break down despite the great lag of consumption behind production, can be explained in only one way: that the war consumed the major portion of the surplus value produced by the workers, so that there was neither a quick accumulation of real capital nor a crisis of overproduction. The war cost the United States 336,000,000,000 dollars. Even if we allow for the rise on prices during the war, this is a colossal sum when we bear in mind that all the capital equipment of the United States in 1938 (railways, factories, public utilities, business buildings, farm equipment, etc) amounted in value to 133,000,000,000 dollars, we can see that if not for the war, this 50 per cent rise in production accompanied by the tardy rise in civil consumption would have resulted in a catastrophic economic crash.

The contradictions in the United States economy that remained latent because of the war will more an more come into prominence. Had towns, railways and industries been destroyed during the war, then for a certain period their reconstruction would have absorbed a large part of the industrial production of America. This did not happen, an more than this, the war and tear of machinery, buildings, etc, was more than covered by new investments during the war. This does not mean that wear and tear in every industry and every individual enterprise was covered by the new investments. As a matter of fact, as far as peace-time industries are concerned, not only did new investments not cover the wear and tear, but they were 4,100,000,000 dollars less for the whole period of 1938-44. Thus, many industries and many enterprises were at the end of the war in need of millions worth of investments in order to make good wear and tear.

A similar effect is produced by shifts in the centre of industry. During the war much of the weight of industry moved to new centres: Texas, the North western Region near the Pacific, and California rose to industrial importance, while the North Western region and the states around the Great Lakes relatively declined. With the end of the war, the reverse process is to some extent taking place. This too, involves large new investments of capital.

The tremendous pent-up purchasing power for consumption goods in America, and primarily durable goods such as cars, refrigerators, etc, is also a notable factor which prevented the contradiction between production and the markets from breaking out in a crisis immediately after the war, or even a few months later. We must not, of course, exaggerate this pent-up purchasing power. During the war, the consumption of everything in the United States rose except for cars and metal household goods. Even so far as cars are concerned, purchases during the war were as much as about half of pre-war purchases. In other words, to make up for the six years of war a production equivalent to three peace-time years is needed, if we are to assume that the American people will recover all the cars lost during the war. In 1941, a peak year of car production, the total price of the cars produced was 3,700 million dollars; for three years this would be about 11,000 million dollars. This is indeed a large amount; but compared with the war production of, for example, aeroplanes (even allowing for the rise in prices), it is not so great. Thus, in one year alone, 18943, the value of aeroplanes in the US amounted to 20,000 million dollars.

But all these factors – the necessity to cover wear and tear of industry, the shift from war to peace production, changes in the location of the centres of industry, the pent-up purchasing power of the people – can postpone the catastrophic outbreak of the contradictions between US productive capacity and the internal market for but a few years at most. Seeing that the national income of the US today is by far the greatest that history has seen, and the rate of accumulation also very high (in 1946 16.5 per cent of the national income went to private capital formations as against 12.1 per cent in 1929), the US must within, at most, a few years be faced with the most gigantic over-production of commodities, capital and labour power. In 1944 the Government Committee for Economic Development estimated that if US production declined to the level of 1940 there would be 15 million unemployed. This year or next, with the high rate of accumulation and the rise in productivity of labour, a decline in production to the pre-war level would throw a much bigger army of unemployed onto the streets than the 1944 estimate.

One means adopted to ease these contradictions is the big military budget. But although the military budget for the year 1946-47 was 12,00 million dollars, even this large sum is but a palliative and unable to bridge the gap between productive capacity and the internal market. US capitalism therefore seeks other means.

Foreign trade will enter as one of the main factors in the attempt to ease the contradictions of US capitalism. But here the US will immediately be faced with an obstacle in that she has to a much lesser extent than British, German or French capitalism, been dependent on foreign trade. Thus, while the volume of US industrial production in 1929 was about 4 times greater than that of Britain, her foreign trade was only 6 per cent grater than that of Britain. Till the second world war, foreign trade made up only about 5 to 8 per cent of US production.

There areas till other difficulties the US is faced with in an attempt to expand imports. British capitalism, which has developed her industry and neglected her agriculture, exports finished industrial goods, and imports raw materials and foodstuffs. American capitalism, on the other hand, developed its agriculture side by side with industry. The US exports not only industrial goods but agricultural goods – cotton, wheat, pork, fruit, etc. She needs to import very few things: rubber, silk, coffee, sugar, woodpulp, copper, tin, and a few other, in the main tropical, products. The difficulty in increasing American exports lies primarily in her unwillingness correspondingly to increase her imports. Her very high customs barriers reflect this.

A country can have a favourable balance of trade for a long period of time in only one of three conditions: 1) that it covers the difference between the export of goods and services and its import of gold; 2) that it covers the difference by paying interest on capital borrowed from abroad; and 3) that it exports capital.

In view of the fact that the US at the beginning of the war already had three-quarters of the world’s gold, the first condition cannot apply to her. To continue to draw the gold to the US from other countries will not solve any problem, but on the contrary will cause grave currency crises in other countries of the world which will have serious repercussions in the US itself.

The second condition does not apply to the US because she is not a debtor country but a creditor country.

The US must therefore fall back on the third condition – export of capital – and in this way attempt to harmonise her necessity for increased exports and inability correspondingly to increase her imports with Europe’s crying need for imports and inability to export. This proves to be the only way she can postpone the explosion of her inner contradictions.

Besides the direct economic interest of US capitalism, her social interests in bolstering up world capitalism also motivate he course in the same direction.

The US was compelled to adopt a similar policy in the years after the first world war until 1929. In the years 1919-29 American exports amounted to 58,176 million dollars while her imports amounted to 43,539 million. The surplus of exports over imports was 14,647 million dollars. According to an estimate by the US Department of Commerce, the import of goods and services to US in 1922-29 made up 83 per cent of all the dollar payments of the US. The rest was covered by goods and services.

After the second world war the role of American loans will be much greater. In the first quarter of 1947 the annual rate of export from US was 20,000 million dollars. At the same time, the import was only 8,000 million dollars. Thus, the export was 8,000 million dollars greater than the import of commodities and the buying of foreign assets. It would be impossible to continue with such a favourable balance of payments for any length of time unless and annual loan averaging 8,000 million dollars were given to cover the difference. This figure corresponded approximately to American estimates that the Marshall plan would give a loan to Europe of 6,000 million dollars annually for 5 years.

Thus, about a third of US exports will not be covered by imports to the US or goods or services, but by an export of capital. This is much greater than the rate which prevailed in the years 1922-29.

American exports on the basis of the US loan, will amount on the average to 15 or 20,000 million dollars a year, i.e., about 5 per cent of the national product. One might conclude from this seemingly small figure that the exports cannot have a big influence on the economic situation in America as a whole. Such a conclusion is entirely erroneous. The cumulative effect of an export of 5 per cent of the national product can be far greater than appears from the small figure alone. Let us shortly outline the reasons for this.

Firstly, if the whole economy exports 5 per cent of its products, it does not mean that every branch of the economy exports only this percentage. Many of the branches are based mainly on export, or are to a large extent based on them.

Secondly, the industries which produce for export contribute to the economic activity of those industries that work for them, such as industries supplying machinery for the export industry, food and clothing for workers in the export industries, etc.

Thirdly, in large scale enterprises where the overhead costs are very big, an addition of even 5 per cent to the sales of the enterprise can yield an increase of much more than this to the profits of the enterprise. It may even make the difference between a profit and a loss. This 5 per cent export can thus fundamentally influence the rate of profit, and as profits are the motive power of capitalist economy, it has the power of influencing the entire economic activity of the country.

Fourthly, the capital exported relieves the pressure in the capital market and in this way, directly and indirectly, operates against the tendency of the decline of the rate of profit.

For these reasons the export of 5 per cent of the national product may mean the difference between slump or boom in America. This will become clear if we look back to the historical precedent of the American loans in the years 1922-29. Although at that time only about 8.6 per cent of the aggregate expansion of the national income was expended on increased purchases of foreign gods and services; and although the increases in the United States receipts from the sale of goods and services accounted for only about 9.2 per cent of the rise in the total national income from 1922-29; nevertheless, foreign trade and the export of capital played a most important role in the American boom.

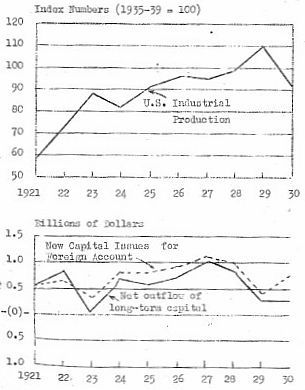

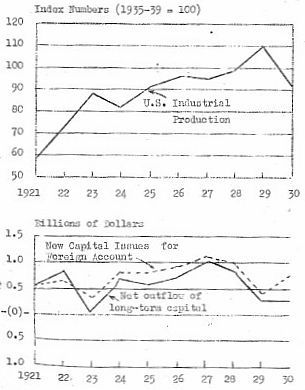

It would be wrong to conclude from this that while the export of capital complements the existence of a boom in the US, it does not at the same time contradict it. Historical experience teaches us an important lesson. In the boom of 1922-29 there was in general a tendency for American exports of capital to increase, but this increase was not of an even tempo. While on the whole, increased production was accompanied by an increased export of capital, the fluctuations in production were contradictory to the fluctuations in the export of capital, thus the years 1924 and 1927, which showed a small stoppage in the rise of industrial production at the same time showed the biggest jumps in the export of capital. To understand this contradictory movement is of prime importance for our comprehension of the nature of the relations between American capitalism and world economy. It is clearly illustrated by the following graph:

|

If not for the boom in America and Europe, the tremendous exports of capital could not have taken place. Conversely, if not for the US loans, the boom of 1922-29 would not have spurted forward and reached the level it did. This is where the boom and the exports correspond. But at the same time, the factor that drove the Americans to give loans, was a stoppage or partial stoppage of the boom. So long as the US capitalist can sell his commodities for good profits in the US market, so long as he can invest his capital and receive a high rate of profit on it, he does not worry about European markets and loans to European countries.

A precondition for big US loans to Europe is the existence of conditions of boom in America as well as in Europe and in world economy. If the economic condition of the world and those of Europe were in such a state that an American loan of a million dollars would allow Europe to produce much more than an additional million dollars’ worth of goods, at a time that the world market was shrinking compared with world production, the US capitalists would not have considered granting any loans. The main worry of the American capitalists in a slump would be how to limit the dangerous unemployment in America, and this they would try to do by undercutting their European competitors, even if it meant throwing the burden of unemployment on Europe. For the American capitalists, in such conditions, to assist in building up the European productive apparatus by granting loans, would be sheer folly.

The US loans are the legitimate daughters of the world boom. But so long as the boom affords the US capitalists handsome profits in the home market, the mood to expand exports, expressed in the granting of loans, does not press so urgently upon them. Finally, we may say that the Marshall Plan, or any other series of US loans to Europe, is the outcome of the combination of two factors: the world boom and the increasing conflict between American productive forces and the inner market. These two are the direct economic factors. But besides them, and of major importance, is the socio-political factor which presses upon capitalism against the assault of the working class and fortify it as an American base for the third world war.

Of course, the American ruling class is not homogenous. The more farsighted section is convinced of the necessity of granting loans to Europe before it becomes a direct economic necessity for US capitalism. Other sections will be driven to this conclusion under the pressure of the increasing economic difficulties of American capitalism itself. Even the direct economic pressure driving towards the granting of the loan will be reflected differently among the different sections of the American capitalist class: those who own export industries will see it in a different light to those whose market is mainly at home, etc.

America’s Favourable Balance of Trade as an Impediment to Extracting Dividends and Interest of Exported Capital |

When a country exports goods, it receives the equivalent in money. The importing country derives this money from its imports. The export of capital, however, sows a different relationship. Here the country exporting capital puts a certain quantity of commodities at the disposal of the importing country without immediately receiving the equivalent in exchange. Only after the loan is realised, does the debtor country begin to pay the interest and instalments on the loan. When a country exports capital, therefore, her balance of trade is favourable, while that of the importing is adverse. This position becomes reversed when the debtor country begins repaying the interest on the loan and the refund. To receive a loan, and pay back the interest on a former one, or to give a loan and receive the interest on former ones, can obviously take place at one and the same time. With an even flow of capital from a country, the amount of interest returning must progressively increase, so that the difference between the annual export of capital and the annual import of interest, decreases. A time comes when the annual interest becomes larger than the annual export of capital; in other words, that the import of goods and services becomes larger than the export of goods and services. This can be postponed only by a progressive increase in the quantity of the capital exported.

The United States, as we have said, is not only the greatest creditor in the world, but also itself the greatest producer of industrial and agricultural products. In what form then, can the United States take the interest and dividends on her capital exports?

The US balance of trade is favourable and with production rising, will continue to be so. The vast majority of American loans will be given to Europe which has for decades, taken as a whole, had an adverse balance of trade. Thus, if the interest on the loans is to b paid and the loans themselves to be repaid, Europe must sell to America in order to get dollars, a process that would give Europe a favourable balance of trade. Since the European countries are mainly industrial, this would require a tremendous increase in their export of industrial goods.

We can see what a dilemma that would place the US. If she (or any country which has a surplus of dollars) imported gods from Europe, the profits of the American industrialists would be trespassed upon; if she did not import goods from Europe she would not really receive her loans back or the interest on them, even though she may become the owner of certain enterprises in the debtor country.

There is an historical precedent for this in Germany’s financial transactions with America after the first world war. In the same years, 1924-32, as she paid reparations amounting to 9.8 milliard marks, she imported capital from abroad amounting to 25 milliard marks. This mean that the American,, British and other capitalists who gave loans to Germany not only lost their loans but in reality took even their reparations not from the German national income, but from the very loans they granted. (As far as France was concerned, she received the reparations from Germany out of the American and British loans.) It was not that the American and other capitalists were unwilling to force out both the reparations and the interest on the new loans; it was impossible, and they had to accept it as such.

The boom years that followed the war, which encouraged America’s export of capital to Europe, inspired every American capitalist who had given a loan with the hope that he would retrieve not only the interest, but also the loan itself. What really happened in those years was that one American capitalist received his interest on his capital exported to Europe out of a new loan given by another American capitalist. This fact was covered by the general anarchy prevailing in the money market. But with the subsiding of the stream of dollar loans in 1928 and its virtual cessation in 1930, the true situation became clearer. Now the debtors could not buy back their debts. This was not only a result of the economic crisis and the slump but also an important contributor to it.

In the years 1919-30, the export of capital from the United States amounted to 11,600,000,000 dollars. The aftermath of the second world war will see a great augmentation of this figure. But with their past experience behind them, the private American capitalists will doubtless be fully conscious of the very meagre prospects of receiving the interest on their loans and the repayment of the loans themselves. From this point of view it is clear that the United States Government will be compelled to intervene in the interests of the capitalist class as a whole, and to take upon itself the main burden of granting loans that are manifestly irredeemable.

The American loans after the second world war have a peculiar character. The general picture is that if a capitalist gives the Government a loan of a million pounds, it can use the money for various purposes. If it serves to build railways, the interest on the loan is derived from the profits on the real capital, in this case, the railways. But if the money is used, let us say, to buy a warship, no interest is derived, as a warship is not real capital. The individual capitalist, however, still receives his interest from the government, even if the warship sinks, and so it makes no difference to him whether his loan serves the government to build a railway or a warship. All he is interested in is that the bonds in his possession are claims on a certain amount of value. To the capitalist class as a whole, however, there is a big difference between the two sorts of capital, real and fictitious, as the only source of surplus value is the real capital. And, other things being equal, the larger and fictitious capital, relative to the real capital, the lower is the rate of profit.

An American government loan, let us say, to France, which is used either to buy new locomotives, machines for industry, etc, or food and other means of consumption which make it possible for the French workers to produce corresponding amounts of surplus value, is for France an addition of real capital. For the American capitalist class, however, there is no difference between this money and those other millions spent during the war on the production of warships: both do not return them any dollar profits, and the interest on them which the government pays to its bond-holders of necessity comes out of the surplus value produced by American workers. From the standpoint of Europe, the American loan is an addition of real capital: from the standpoint of the United States capitalists, it is only an addition of fictitious capital.

The American loans to Europe are a combination of two contradictory phenomena; the one peculiar to a capitalist boom, the other to a “war boom”. In a capitalist boom there is an accelerated accumulation of real capital accompanied by an accumulation of fictitious capital. During a “war boom” the accumulation of fictitious capital receives a tremendous spurt while the accumulation of real capital is retarded, or even transformed into its opposite, i.e., that wear and tear and destruction assume larger proportions than new investments. These two phenomena are expressed in the American loans thus: that from the standpoint of the United States, the amount given as a loan is extracted from the surplus value produced in the United States, and to that extent it negates the accumulation of real capital in the US. Because of the contradictions of world capitalism in the world market, it is not excluded that such a “bloodletting” will indirectly encourage the accumulation of capital in America. From the standpoint of European capitalism, the loan is indirectly and indirectly an addition to the real capital, and as such contributes to the conditions necessary for a real boom.

This double character of the American loans explains their contradictory influence. The fact that during a war, fictitious capital relatively increases, does not mean that the post-war economy is headed for a crisis: on the contrary, the conditions this increase brings about – a lack of means of production and means of consumption, under-supplied markets, etc – are precisely the prerequisite of a boom. Now, if the American loan were simply an addition to the fictitious capital, their immediate effect would be accelerated economic activity and therefore a rise in profits in America. In the final analysis, with a turn in the economic cycle towards crisis and depression, the large amount of fictitious capital would have been an added burden on the declining rate of profit. But actually in the long run, the loans will have an even worse effect on the economic situation of the united States, as they will serve not to produce warships which yield no profits, nor new American railways, but to construct French or English factories which (while never able to transfer part of their profits in the form of interest to the United States) will sooner or later appear as competitors on the world market. To grant these loans may thus seem an illogical step for American capitalism to take. But it is the result of the increasing conflict between the productive forces and the capitalist relations of production, a conflict expressed in the overwhelming wealth of United States capitalism and in the relative decline of Europe as against America.

The expansion of American imperialism differs in many fundamental points from the expansion of all its imperialistic predecessors. Let us compare American imperialism to British imperialism.

Britain conquered the majority of her colonies at a time when capitalism was progressive, and still struggling against declining feudalism. American imperialism steps on the stage of history at a time when capitalism is writhing in the throes of its death agony; and its struggle is to bolster up the declining capitalist system.

British imperialism derived a higher rate of profit from its investments in the colonies than was yielded in the “mother” country. US capitalism is so rich that it cannot absorb any considerable portion of the surplus value produced outside its borders into its economy.

The Empire gave Britain a cheap source of raw materials. America can produce herself most raw materials more cheaply than any other country.

Britain’s colonies served her as vantage points where she could market her goods with the minimum of danger of being ousted by other capitalist countries; the colonial markets were monopoly markets for her. American capitalism is so technically advanced that it does not need any vantage points in order to stand its ground in competition on the world market.

Britain subjugated pre-capitalist countries where the conditions for national movements had not yet been brought into being. It was the historical function of British imperialism to bring the national movements into being.

1. As far as we have been able to ascertain the other two articles were never published. Indeed they may never have been written, as at the time of writing Cliff was wrestling with the theoretical problems connected with his study of Stalinist Russia and with major personal problems – the Labour government had just denied him the right of residence in Britain and he was frantically searching for another country to go to.

Last updated on 13.1.2009