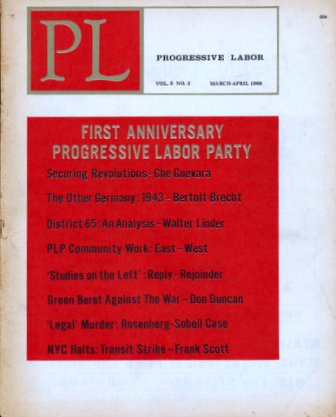

First Published: Progressive Labor Vol. 5, No. 3, March-April 1966

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Community organizing, as opposed to industrial organizing, is not a new concept for the American left. Since the Great Depression, American radicals have attempted to organize around community issues in working class neighborhoods, in black ghettos and Latin barrios, from Brooklyn, N.Y. to Brawley, Calif. Most often, organizing has been done around certain key issues– housing, welfare, unemployment. During the thirties, the Communist Party USA organized unemployed associations and tenants councils all over the country. In recent years, so-called “civil rights” groups in many areas, recognizing that, despite all the mass action, the movement had no real communication with the black masses, have gone into grass-roots organizing. Likewise, the “New Left,” replete with its non-ideological bourgeois idealism, has moved onto the scene in such distant points as Newark, New Jersey and Oakland, California. The CPUSA has picked up the ball again, waging lukewarm struggle on welfare outrages and hot lunch issues. And the revolutionary left, whose approach is the subject of this article, has also reared its head, on both coasts, in working class communities.

The ruling class recognizes a good thing when it sees it. It too is in the act, with a comedy called the “War on Poverty,” a venture into “community action,” in the futile hope that the potential revolutionary leadership which exists in every working class neighborhood can be absorbed and thus confined–before it matures.

To work with the people is to learn from the people. The community organizer makes organizational gains only in the degree to which he learns from the people. Much as the individual, it is the obligation of the vanguard party to become for the people both pupil and teacher, to learn from the people and to develop for the people the means and forms of revolutionary struggle for class liberation.

In On the Party, a document prepared by M. Rosen for last April’s founding convention of the Progressive Labor Party, the function of democratic centralism, the lifeblood of the party, was explained in the following way: “Democratic centralism enables us to gather the ideas from the masses, fashion them into programmatic and strategic positions and then go back to the masses with our plans. It is...this...theory that enables us to draw closer to the masses, enabling us to develop our theory, strategy, tactics, while preserving the movement from the blows of the enemy...”

In some respects, the concept of community organizing clashes with orthodox Marxist-Leninist notions of organizing the working class for revolutionary struggle. Community work often–but need not–subordinates the importance of the shop to the home, places undue importance on geographical rather than economic location and, almost always in minority group ghettos, underscores the class-national contradiction.

Nonetheless, the “panoramic” vista which community organizing affords has numerous strategic and tactical benefits. It provides, among other things, an opening to many doors–and the opening of many doors is a firm basis on which to assess what conservative and what progressive forces exist in every working class concentration.

Often, work in a neighborhood around such seemingly minor issues as housing repairs becomes a springboard into a more vital area of class contradiction–the shops, a sell-out union, etc It must be acknowledged that such forms as community struggle ordinarily are never revolutionary, at best they are militantly reformistic. To win a rent reduction, immediate repairs, a stoplight, is only to win a concession and not socialism.

Our main task as community organizers is to win the people to revolutionary socialism. When such concessions as we wrest satisfy the people, then we have come a step closer to insuring the necessity of the party.

Leaky faucets and late welfare checks–these are only minor skirmishes. But each struggle, no matter how small, no matter whether it results in victory or defeat, prepares the people for greater struggle, for revolutionary struggle. This is essential in building respect and confidence in the party, in building a refuge among the people.

These are not untested premises. Our conclusions are drawn from experience over the past year in the Mission district of San Francisco.

It was out of a city-wide PLM collective that the Mission club came into being last January. None of the members lived in the district when the club was formed. Today we all do.

The Mission district was chosen as an area for community work because of certain class and national considerations. Although study of the census tracts yielded a somewhat higher degree of unemployment and a lower median income in the Negro ghettos of Hunters Point and the Fillmore district, it was obvious that as an all-white club our effectiveness would be minimized in a black neighborhood. The addition of Spanish-speaking members to the club made the Mission district the best bet for us.

The Mission district is a working class community with a high percentage (60-70) of Spanish-speaking people as its base. This was not always so. For many years, especially during the great labor struggles of the early part of this century and into the thirties, the Mission was inhabited mainly by Irish and German workers. Today, the Bradys and the O’Neils are nameplates on local bank officials’ desks. The predominent ethnic group, the Spanish-speaking community, unlike the large homogeneous groupings of Puerto Ricans in New York, Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles, etc., is quite fragmented in San Francisco. While residents of Mexican descent still appear to predominate, the Nicaraguan and Salvadorian population is fast expanding as are the Guatemalan and Costa Rican communities. The Puerto Rican population is shifting into San Francisco from other northern ghettos. Virtually every country in Latin America is represented in the Mission in some number.

Although these various national groupings are seriously divided by traditional rivalry, they are to some degree, united by the cause of their emigration–United States imperialism. While a small proportion of San Francisco’s Spanish-speaking population is in actual political exile, many more are here because North American imperialism has turned Central and South America into a virtual slave market. Each year, thousands of latinos come north– most already have relatives in the city–hoping to go home with the fabled gold of the gringos. How many arrive here each year on the basis of what Hollywood exports to Latin America? For most, awaiting at the end of the road are not the new cars and kitchens which Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has sold them, but rather the sweatshops and slums of the Mission district.

We remember a Salvadorian, M., a bookkeeper from San Salvador, a product of the petty bourgeoisie who, in 1961, frustrated with the severe limitations that gringo control placed on the national economy, put together $700 and moved his family North Last month, he went home with nothing in his pocket. For four years he had been out of work more often than not. His wife had supported the family on a nurse aide’s pay. M. still spoke little English when he went home –but in his throat the taste of retribution was bitter.

The proletarian history of the Mission is rich. Many locals were organized right in the district. The Labor Temple still stands on 16th and Capp–we leaflet it about once a day. Local industry, while moving into other areas, still prevails as a major source of employment for residents. Although some of the industry is heavy, this is not basic to the economic structure of the community. Most industry is light, often connected with agricultural production, very often low-paying work–garment work, laundries, woodworking shops, food processing plants, canneries, bakeries, tanneries, etc. Agriculture and agriculturally related industries are one base of California economy and significantly, the one in which workers are either organizing or re-organizing.

Despite the clear necessity for work in the shops, our lack of roots in the community forced us to begin organizing in the area of housing. Knocking on doors is the easiest way to begin...

We began with too many preconceptions...door to door agitation about the “thieves” who rob us of rent for roach-infested apartments–although we did not even live in the district...many of our initial propaganda tracts were copied all but verbatim from CHALLENGE and other New York City source material...this was–and to a certain extent still is–a measure of our political maturity...as a result of this lack of experience and proper analysis the only lessons learned from our first months in the community were largely negative ones. We did find apartments for ourselves however...

Although the landlord-tenant contradiction is perhaps a secondary one, it is also an antagonistic one–especially in San Francisco. With one of the highest rental rates in the country, which has no rent control law, little public housing and where tremendous profits are being reaped on land sales–often on the resale of slum property to the various urban renewal combines which are bent on making this town the “financial capital of the USA” (or so indicated a recent Life article).

Lack of a central base of operations hampered our activities for a long while. In the beginning we would meet every evening in a 16th Street donut parlor. Many months later we discovered the shop to be owned by a notorious slumlord whom we had to picket. As a result of that picket line one family received free rent for over three months, and one of our members lost a job.

Too often, during those first months, discussions with tenants escalated from immediate housing conditions to imperialism in the naive hope that we might find people in agreement with our total political line. Too often we tried to cover our newness to the community with slick generalizations. Our contacts were few and short-lived. We participated in little and led no exemplary struggle in the Mission district during this period.

Throughout February and March, we were pre-occupied by the bombings of north Vietnam. Night after night, we held street meetings to “explain” to the people the nature of U. S. imperialism in Vietnam or Selma, Alabama. These “explanations” consisted of hour-long harangues, desperate exhortations to “wake up,” which mostly antagonized the workers waiting at the bus-stop to go home. Too often the harsh realities of life in San Francisco, and especially the Mission district, were glossed over in the “interpretations” we made. Although contacts were made during this series of street meetings, little chance of involving them in the work was possible. Our basic error at this time was an inability to learn from the people what the real problems were and what forces were available for their solution.

Then, one evening in March, we knocked on a door down on Shotwell Street and found rats. “Rats!” yelled one of our members “They got rats!” After three months of desperation we had at last discovered rats (they turned out to be mice), and this discovery turned into our first rent strike...

Rent strike is a notoriously un-dramatic way of struggle. It is usually a private gesture, a kind of secret pact between tenants to break laws which are heavily loaded in favor of the landlord. The danger for working class tenants–especially those with large families–is great. The landlord always has an option to evict if the rent is not paid. Should it be a matter of necessary repairs, the realtors often comply and then double the rents. In the end, the main gain which is made is the provisional organization of the tenants. Often this organization collapses once the reason for its existence–rats, roaches, no hot water, rent gouging–is resolved, or defeated. With our first rent strike, the need for an intermediate organization between the party and the individual rent strike committee became clear.

Soon after the founding convention, the Progressive Labor Party set up a Mission district center. We officially opened shop with a May Day party. On May 2, early in the morning, a large fire occurred which left six families without any personal belongings whatsoever. It was on the same street where we had organized our first rent strike. We had been in the burnt-out building selling and trying to organize around the wiring hazards which finally caused the fire.

That day the need for a mass organization of tenants became immediate. We had learned from our first rent strike that one struggle against the class enemy did not make the necessity of a revolutionary party very much clearer to the participants. No one in the struck house was prepared to make a commitment to the PLP., Moreover, it was becoming increasingly difficult to consolidate organizational gains. Once tenants won the repairs they wanted, interest seemed to die. We needed a form which would involve tenants in mutual defense and lasting struggle, which would involve them in struggle transcending their own immediate surroundings.

The afternoon of the fire, in front of the burnt-out building, we called for the formation of a tenants’ union, an organization which would defend tenants against such outrageous, negligence as caused the fire. The leader of the rent strike found a charred baby-shoe in the rubble and passed it around. The $13 collected paid for the first Mission Tenants Union leaflet; clothes were collected throughout the neighborhood and those which the burnt-out families could not use were later sold at a rummage sale from which the proceeds were divided between the MTU and the tenants who had lost everything.

Since May, the Tenants Union has grown to include over 120 families actually represented and many more who, for one reason or another, have not signed an authorization card giving us power to negotiate and enter into collective bargaining agreements with their landlords.

The term Tenants Union is not just the usual plagiarism. The American labor movement was organized as an economic defense against the exploitation of the working by the ruling class. By uniting and refusing to work at a subsistence level, American workers have found a bargaining strength 4hat enables them to sell their labor power for what passes as fair wages and working conditions. In the same way, the Tenants Union provides strength in association for tenants which employs, through rent strike, the threat of cutting into the landlord’s rate of profit in order to gain a fair rent ceiling and decent living conditions. From this, it becomes clear that, like a labor union, the Tenants Union is a reformist rather than a revolutionary form. Although the concept itself is sometimes termed “revolutionary,” the MTU neither attempts to abolish the profit system or seize state power.

That the average landlord is a class enemy is a lesson that every working class tenant learns through MTU struggle. Slumlords run the gamut in profession from crooked donut dealers to prominent civil rights attornies. One day one of our comrades happened to be standing in front of a building on rent strike with a couple of mice in a coffee can– the mice had just been trapped in the building. Suddenly, two of the realtors who controlled the building appeared on the scene with the health inspector. Comrade J. whipped out the mice and showed them to the operators. “He’s lying!” shouted one to the Health Inspector. “He’s brought those mice all the way from the Fillmore district (the Negro ghetto) and I’m going to have him arrested for violation of the health code.” Just then a healthy roar of laughter went up from the building; all the tenants were hanging out the windows and watching the show beneath.

One member has a gas leak, the landlord is summoned. “Oh everything’s all right,” he smiles, “but what you guys need is a little more fresh air,” and he proceeds to pull the window wide open to let the gas escape...

In the Fillmore, a tenant complains about the lack of a back door in his dilapidated flat, so the landlord comes around and removes the front door.

Many of our members have been involved in struggle of varying degree for the first time in an organized way. From getting the Post Office to clarify a street address to taking on the Apartment House Owners’ Association, such as we now are doing with a key five-family rent strike, two blocks away from City Hall. This present struggle has all the elements necessary to educate the public about the nature of the ruling class–absentee ownership (the building has had six owners since November), big realty concerns, rent gouging (the rents were upped from $60 to $115), three eviction notices, picket lines, collective bargaining and a landlord who dabbles in prostitution and skid row hotels.

That the Apartment House Owners’ Association should have felt so threatened as to pit its legal and financial might against our tiny organization, in support of so shady a landlord, is as much proof of the necessity of such a form as the tenants union, as it is a test of the kind of success we’ve been having. A recent column in a local newspaper, written by a spokesman for realty interests across the city, indicated this fear plainly by urging the formation of an independent tenants organization, one which was not guided by the thinking of an openly revolutionary party. The writer, a former candidate for local office, conceded that we were “filling a vacuum” for many tenants. Any time we get a reaction such as this, we know we must be on the right track.

But although our work has proven to be largely positive, there are certain mistakes and wrong assumptions that are holding us back. The lesson that landlords are bent on the exploitation of the working class is easily learned by MTU members. Many of the harder ones–lessons about the nature of imperialism, the necessity for a revolutionary party, are not Although we sell many copies of Spark in the community, we have obtained very few subscriptions. Some members have been recruited through MTU ranks but the gains are small and the commitment somewhat hesitant. Our work in the community, like the work of the rest of the party, while quantitatively enormous, has much to gain in quality. The several criticisms which are most often raised reflect a failure to couple theory with practice.

We have failed to involve nonparty people in organizational work. We still tend to assume too many of the secondary tasks of organizing. Writing and passing out leaflets, running of social events, tracking down landowners in the City Hall Archives–these are only some of the activities that non-party people should be involved in. This failure to extract consistent commitment from the community severely limits our work–especially when all club members are employed.

Nonetheless, involvement of non-party people can be a perilous process if those involved do not have some vital stake in the struggle at hand. It is far more important to involve–however tentatively–a tenant who has experienced eviction in a fight against evictions, than it is to ask the often much more expert student or minister to help. Where ever possible, we must strive to involve working, as opposed to professional, people in the organizational work of solving working peoples’ problems.

In the process of development, we have had the cooperation of several clergymen on certain projects. No matter how genuine their idealism is, clergymen are not consistent. When it comes to action, they often are not there. One reason is that many of these “new” clergymen, although acutely agitated by the hypocrisy of the established church, have no ideology which makes them see the prevent such resistance from crystalizing around class issues, by providing token reform measures. Such preventative measures are doomed to failure.

One decision which continually plagues all honest revolutionaries is whether or not to participate in limited reform programs. It has been our analysis that while the Poverty program can never succeed, the false hopes spread by the sound trucks and leaflets, the newspapers and television, etc., could best be exposed by working from within.

Because of our open and real contact with the people, there was an attempt by liberal forces in the district to absorb (and thus neutralize) us from the very first meeting. One comrade was appointed to the interim executive board, which was then in the process of setting up district-wide elections to the permanent board. From the outset we carried the fight for total control of the board by the poor to the people, through leaflets, public meetings, etc. When the elections were eventually set up on a compromise basis, our basic line was that to tight a war on poverty, we must fight the poverty makers. Although two of our comrades and one MTU member were elected to the board running on a peoples’ slate. Lack of community confidence in the program limited the effect of our line. Since elected to the pursuing various ways of bringing the neighborhood board into conflict with City Hall. Such conflict must be created if the people on the street are going to learn any lesson at all from the War on Poverty.

In the coming year, we must seek ways of further politicizing our work in terms of an open revolutionary line. Too often we have compromised by taking reformist positions.

Clearly, the primary contradictions within the community are economic. Unemployment and under-employment, housing, welfare–all these place a terrific burden on the workers of the Mission district. Questions of sell-out union leadership and closed-book unions are some aspects of the economic contradictions that have yet to be fully explored by us as communists. During the coming year, employment problems and shop work may well overshadow tenant organizing as our primary task.

One factor involved here is the new Bay Area subway system (BART) which will soon begin tumbling low-rent (albeit, substandard) housing here in the district. No relocation plans are proposed. Moreover, BART, which initially offered 60,000 new jobs to the Bay Area, in an effort to win multi-million dollar bonding, has come up with only 7,000 openings so far. With an 11 per cent unemployment rate in the district, a united front is in the offing, to demand construction jobs for unemployed Mission district laborers.

Recently we held a meeting on the question of low pay and high rents. One central point raised was that such minority group concentrations, as occur in the Mission district, do so for the purpose of geographically confining a source of cheap unskilled labor. This theoretical understanding of the relationship between substandard pay and housing must be put into practice in the coming year.

Our one major thrust into the shops this past year, has been at a local Levi-Strauss plant. This factory employs some 300 women mostly of Central American descent, most of whom are residents of the Mission district women, because machine sewing is almost a necessary home skill in all of Latin America, often find work in the garment industry. A year ago, an automated speedup of certain machines in the plant forced a wage cut upon the women. Their local, 131 of the United Garment Workers, refused to back up the women’s demand for a return to the old scale. As a result, during the last six months the women at Levi-Strauss have pulled off four separate work stoppages and two marches on the Labor Temple to protest the union’s indifference. From this struggle, a natural leadership, as well as plant organization, has evolved. Thus, when elections in the local were scheduled, the Levi-Strauss plant was prepared to put up its own candidates and wage a winning campaign for office. Comrade C, who made contact with the women early in the struggle, is given credit for having guided the rank and file candidates to victory.

Nonetheless, while having one organizer on the outside has strengthened our image, an absence of comrades on the inside of the plant hasn’t made the situation particularly fruitful in the area of organizational gains. We sell Sparks and issue leaflets (most of the copy we get is good). We are respected there.

Comrade C.’s main opponent for the women’s loyalty is a notorious opportunist who regularly announces his “line” in a local Spanish-language newspaper. One day, the opportunist, a Dr. 0., was talking to the women. “You cannot trust C. He is a communist.” “That’s alright,” the women replied, “we trust him more than we do you, you are a crook.”

The contradictions intrinsic to nationalism, although secondary, play a tremendous role in the community. This was pointed out by the fearful reaction of many Latin Americans during the Watts Insurrection. In the coming year, this contradiction can only become sharper as black people are driven to the Mission for low-rent housing by re-development plans in the Fillmore district. Two possible projections are classes in minority history in the Spanish-speaking club in the Mission. This is not enough. Integrated struggle is which we must be moving, if we are going to resolve this contradiction. This can be a difficult task.

In one building, a number of Spanish-speaking tenants banded together to fight for the return of outrageous deposits charged two Negro families. The black families, however, always refused to attend meetings in the building-even after the deposits were recovered. Indeed, one of the families moved out of the neighborhood after the victory. “Things were getting just a little too hot around there for us,” he said.

At one meeting of the MTU, we called for three volunteers, black, Latin and white, to run down a complaint on renting discrimination. The white Protestant American went first and was denied a key by the realtor. The two others obtained it and had to do some fast talking to get out of renting the apartment. That these three workers could make such motions was a victory, but this was before Watts; it has been more difficult since.

During the past year, we have slighted the youth of the Mission. They are a potential force for change. The structure of the community confronts them with a whole series of oppressive alternatives, not the least of which is the Police Department. Every day the cops roust kids at the Doggie Diner, on Mission Street, across from the Center; yet, despite these things, our contact is very shallow.

Every day the papers list the names of boys from the district’s high schools who have been killed in Vietnam. American working class communities from Maine to California are faced with this harsh reality. High unemployment rates among working class youth means high enlistment rates in the armed forces. In the coming months, through Spark sales and personal contacts, we must begin to organize against the war in the local high schools. The potential for organizing is there.

During the recent poverty elections, some neighborhood kids– “drop-outs” in ruling class jargon–caucused on a neighbor’s front steps and nominated two sixteen year olds for the area board. Both these kids took alternate slots and are now functioning on the board. This political move by the kids themselves, independently, without asking or waiting for anyone’s advice or “help,” is an indication of what we have to work with.

But the most important work which must be done in the community is the carrying out of the main task–the building of the party. In this respect, we must be prepared to wage militant, if reformist, struggle on every front–rent control, the war in Vietnam and on poverty, the Welfare Department, the sweatshops, the cops. We must be prepared to work more openly as communists, to combat intensified redbaiting by long established political entities in the community–the Mexican American Political Association, the Spanish-Speaking Citizens Foundation–-to whom we pose an increasing threat. We must strive for an understanding in the community of our total political line, and thus, for an understanding of the necessity for the building of a revolutionary vanguard. Finally, we must strive for consolidation and expansion of our base, increasing respect for revolutionary socialists through our work, and the potential of increasing the party ranks.

16th and Mission...Friday evening... it was a pretty hot street meeting... Comrade R was on the box shouting to the crowd at the bus stop about the War in Vietnam...a self-styled preacher stood below him...at his elbow... howling Jesus Saves...in front of the drug store an argument was developing....“These people are communists” said a fat gentleman in Spanish...“No, no” protested the old Mexican laborer who stood next to him, a little drunk... his wife was the leader of a rent strike committee and he knew us, though not well. He turned to Comrade E. for help...“You are not a communist, no?”...“Yes, we are...we are revolutionaries...we believe in socialism...”...“But you fight for the people,” the old man answered in amazement...